What’s With the Underwhelming Military Response on Maui?

U.S. forces historically have had a commanding presence in the aftermath of natural disasters, but many are wondering, “Why not in Lahaina?”

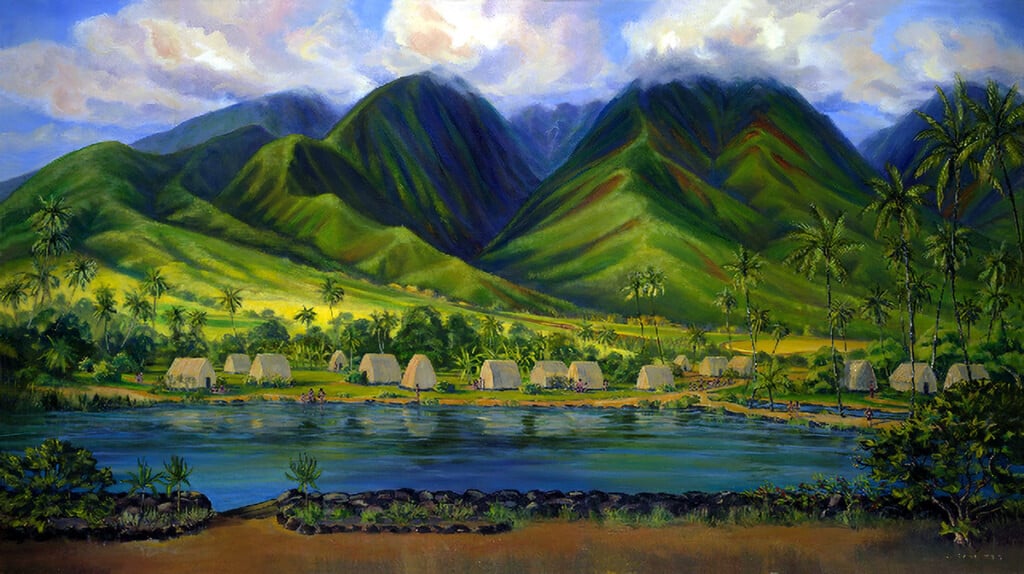

Photo: Army National Guard Staff Sgt. Matthew A. Foster

“Skimming low over the calm blue Pacific and over acres of roofless houses and broken palm trees, military C-130 relief flights landed in a daylong stream Friday on the lush tropical island … forming the only link to the outside world for residents devastated … on Friday. Loaded with generators and communications equipment as well as military rations and bottled water, the relief flights brought the essentials of daily life to 55,000 residents and thousands of stranded tourists.”

No, this is not the beginning of a story about Lahaina. It’s the opening paragraph of a story in The New York Times from Sept. 13, 1992, after Hurricane ‘Iniki battered Kaua‘i.

31 years ago, viewers glued to screens across the world saw a reassuring sight along with the coverage of distraught victims and destroyed neighborhoods: our men and women from the U.S. military, arriving in an endless array of planes, helicopters and ships, hitting the ground to conduct search and rescue, unload equipment and supplies, provide first aid, erect shelters and hand out meals, water and clothing.

That wasn’t what we saw after Lahaina’s Pompeii-like destruction Aug. 8 and 9. Instead, the nonstop compelling images were of West Maui locals making it happen, creating a supply chain of trucks and cars. When those were blocked from entering West Maui by the authorities, they improvised a miniature Dunkirk of inflatables, fishing boats and personal watercraft to ferry donated water, food, medical supplies and more.

In this era of social media proliferation, a preponderance of coverage from Lahaina and West Maui came from citizen commentators, who called out the state and especially federal response. One of the louder questions was raised by a couple of dazed survivors wandering a deserted Front Street the day after the fire: “Where are the uniforms? Where is the military?”

It was a reasonable question. There are 12 military bases in the Hawaiian Islands, including a Coast Guard station on Maui. Wheels up to wheels down, Maui’s airport is a 23-minute flight away from Honolulu. Yet, there was no media—and no social media posts—showing a large military reaction. Were they not on Maui at all?

Table of Contents:

- A Marine’s Perspective From Hurricane ‘Iniki

- Where Was the Military?

- Changing Disasters and Responses

- News Breaks on Social Media

- First Night Response: Tuesday, Aug. 8

- Wednesday, Aug. 9: Morning After

- Two Big Lifts

- Facing a New Disaster Reality

Photo: Army National Guard Staff Sgt. Matthew A. Foster

A Marine’s Perspective From Hurricane ‘Iniki

Waterman Mel Thoman, known as @wedgemel on Instagram, posted a video that expressed his bewilderment. “I was here for ‘Iniki in 1992,” Thoman says. “It just blew apart Kaua‘i. I was in the Marine Corps on O‘ahu with a helicopter squadron. As soon as it passed, we organized and did 10 to 12 sorties a day from O‘ahu to Kaua‘i, O‘ahu to Kaua‘i. We brought water, food, doctors. And it never stopped for two months.”

Thoman pauses for a breath, then resumes: “My question is, where is the military? Where are the helicopters? Why is it the locals having to do everything? Why is it Kai Lenny? Kelly Slater?”—name-dropping two famous surfers who took part in an immediate, impromptu and extraordinary response by the surfing and boating communities, which used their expertise to bring in supplies up-coast from Lahaina’s burnt-out docks and ocean frontage.

Where Was the Military?

It turns out the military was there, arriving as Lahaina burned. But you didn’t hear about it. They were out rescuing and responding, just not sharing their efforts on social media. But, as we’ve come to see, in the battle for messaging, no entity can afford to neglect the expectations of incited Instagram and TikTok viewers without risking blowback.

After the golden hour of rescue passed, what happened in terms of the military response feels less satisfying. They are, after all, the only feasible source of an immediate intervention in a disaster of this scale. The Federal Emergency Management Agency would receive President Biden’s approval to launch a federal disaster team that very day, Aug. 9, but wouldn’t open its first center on Maui until Aug. 15.

After looking into the question—which wasn’t easy, given that multiple public information officers were understandably too busy to respond—it does seem that in the first 48 hours, there was a gap in which dazed and unhoused survivors, left to shift for themselves, were abandoned by the government. It was a natural time for an ‘Iniki moment.

Instead, the impression overall is that the military response was adequate, not overwhelming. And in disasters of this nature, we’re used to being overwhelmed.

Changing Disasters and Responses

However, sometimes the fault is in the stars; other times it’s with us.

The first thing to acknowledge is that disasters seem to be changing. Lahaina wasn’t ‘Iniki or Guam. The latter were wet hurricanes that allowed for advance preparation.

The fire hurricane, or super-wildfire, is a relatively new phenomenon that is much harder to predict. It arrives without warning, is more lethal and tends to leave utter desolation in its wake. Paradise, California, was its bellwether, a remote suburb built in a drought-plagued wilderness with only one road for evacuation.

SEE ALSO: What Other Areas of Hawai‘i Are at High Risk for Wildfires?

Second, disaster-wise, everything is happening everywhere at once. Along with Maui, Hawai‘i Island and O‘ahu, major fires this week include those in British Columbia, the Yukon, Spokane, Greece, Italy, the Canary Islands and a dozen other places. This week, the Atlantic is looking at four tropical storms or hurricanes; California just got its first tropical storm landfall in 84 years.

Third, our politicians and governments have failed to deal with climate change issues like wildfires. Studies have been done, even one that literally predicted Lahaina. But it must be said, politics often fails to act because we don’t want it to. We want more suburbs in wild places. We want to move ever closer to nature and to fire and flood and storm surge. It’s ingenuous to pretend otherwise.

Fourth, government and the media must get out in front of events faster. At the same time, the public must harden against the depredations of social media and fake news.

Photo: Army National Guard Staff Sgt. Matthew A. Foster

News Breaks on Social Media

The vast number of users in a disaster now share information immediately on social media when disaster hits. Social media really earned its spurs (again) by providing real-time commentary by people caught in the center of something too great and fast-moving to be comprehended by official channels, whose messaging had utterly failed. The streams were verifiable, time-stamped and damning.

Damning because, for Maui’s government, this has been a broken trust, a failure of systems, leaders, implementation, communications and long-term strategy that doomed more than 100 and torched an entire historic town. It was through social media that we first learned that the Maui head of emergency management was at pau hana at a hotel in Waikīkī; the Maui fire chief was on vacation; and the mayor of Maui literally didn’t know Lahaina had already been consumed while delivering a platitudinous live commentary. Yes, it was rumor when we first read it, but those on social media had details, and they were sharing before local mainstream TV and news got around to broadcasting, a week later, what had become obvious.

This lag ceded the stage to the usual suspects, who came out in force: conspiracy theorists, anti-government doom-scrollers and paranoids, the nihilists who love to stir hate and confusion, as well as sincere folks confused or stirred up to amplify their misleading and outright fake news. The troll swarm helped themselves to others’ feeds and posts and reposted them with their own messages and agendas.

We live in a land where disaster is always near. We need to do better next time, and the next, and the next. The only way to improve our responses is to ask questions, sift data, toss the chaff and follow up with conclusions that are actionable.

What follows is a reconstruction, as best as could be determined from official Defense Department press releases and social media, press sources, state and county announcements, and verified social media.

SEE ALSO: Latest on the Maui Wildfires

First Night Response: Tuesday, Aug. 8

The first fires were in the Uplands of Maui, just after midnight Monday, and required a widespread effort from the Maui fire department. A fire above Lahaina that had been reported 100% contained Tuesday morning flared back up around 2:30 p.m. At 3:43 p.m., Hawai‘i Lt. Gov. Sylvia Luke issued an emergency proclamation for Maui and Hawai‘i counties.

Kula and Olinda would receive evacuation orders, but not Lahaina. Video showed the waterfront engulfed by smoke by 4 p.m., and by 5:13 p.m., the fire had reached the waterfront. Twenty minutes later, people were sheltering in the ocean and broadcasting their distress.

At 5:45 p.m., the U.S. Coast Guard in Honolulu received reports of “multiple persons in the water needing rescue after taking shelter from fire and smoke in Lahaina.” An MN-65 Eurocopter Dolphin helicopter was launched from Barbers Point on O‘ahu; the cutter Joseph Gerczak was diverted to Lahaina; and the Coast Guard’s Station Maui dispatched a 45-foot Medium Response Boat. In Kāne‘ohe, Helicopter Military Strike Squadron 37 dispatched two MH-60 Sikorsky Seahawk helicopters.

The Medium Response Boat arrived at 6 p.m. Already responding were three local women, sailors who run boat tours out of Lahaina. As smoke and flying embers descended on the waterfront, Captain Chrissy Lovitt; her first mate and wife, Emma Jean Nelson; and fellow Captain Lashawna Garnier took a 10-foot inflatable skiff and set out in 80 mph winds to pick up swimmers and transfer them to a 120-foot wooden sailing yacht moored far offshore. Via VHF radios they contacted the Coast Guard. The “fire sisters,” as Lovitt calls her courageous band, made five trips. “We all did work with the Coast Guard and a Coast Guard swimmer, doing what we could to pluck those kids out of the water.”

Lovitt’s last trip of the night nearly proved fatal. A wave flooded their skiff and hurricane-force gusts began to blow them out to sea in the darkness. They drifted close enough to the moored yacht for a line to be thrown and secured, thus rescuing themselves, only to watch Lovitt’s own boat, Wahine Koa, burn at anchor. All told, 17 people, some of them visitors, were rescued from the water that night and another 40 located ashore.

On Tuesday night, the Hawai‘i National Guard and its aviation wing was activated. But its large and ungainly CH-47 Chinook helicopters aren’t all-weather Search and Rescue aircraft like the Dolphin and Seahawk, able to fly in hurricane-force gusts. There also weren’t very many of them. As reported by ABC News, “the number of Hawai‘i National Guard helicopters available to assist was less than normal since many of them were in transit back to Hawai‘i, after having participated in a large exercise in Louisiana.”

Wednesday, Aug. 9: Morning After

More Coast Guard rescue boats were rushed onto a second cutter to aid in the search and recovery operations. By morning, National Guard land units were deployed for traffic control and firefighting, and to assist the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency. The state’s Air National Guard and the active Army’s 25th Combat Aviation Brigade sent almost a dozen helicopters for search and rescue and to fly 58 “bucket runs” from local reservoirs, dumping water on fires that continued to burn in Lahaina, Kula and elsewhere. Luke overflew Lahaina on a Coast Guard C-130.

Also on Wednesday, the National Guard sent Honolulu Fire Department vehicles and personnel to Maui in the giant bay of a C-17 Globemaster. More helicopters from the 25th on O‘ahu were added for firefighting, with naval aviation units also standing by if needed. A KC-135 Stratotanker brought in more than 30 National Guard search and rescue team members, including active-duty and National Guard personnel integrated into a Chemical Biological Radiological Nuclear and Explosive enhanced response package, and 3,700 pounds of supplies.

Two Big Lifts

The following day, more Globemaster runs delivered disaster relief cargo. During the same period, large public donations of food, water, clothing, medicine, generators and more poured ashore, much of it, according to boat tour operator Lovitt, landed at the Kahana Boat Ramp.

Three days after, the National Guard and the Maui and Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agencies were making room for FEMA, which had 150 people on the ground by Aug. 12. FEMA, of course, is not the military. Nor does it try to do everything, instead amplifying and augmenting its work by coordinating with National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster, an umbrella group that includes reputable community and faith-based organizations. Many of these were already working with the locals doing resupply at Kahana and elsewhere before FEMA arrived.

By Aug. 14, five days after the fire, FEMA had 416 personnel working with the Red Cross and other organizations, in comparison with 600 on the ground one week after Hurricane Mawar, which struck Guam May 23. In Gov. Josh Green’s Aug. 14 “whiteboard address” he noted the FEMA team, the 175 National Guard he had approved, and Biden’s immediate approval of a disaster request. He gave a rundown of how many had been housed (100), how many hotel rooms were immediately available (402), and noted that discussions were ongoing with Airbnb about providing housing.

Green concluded by noting that so far 750,000 pounds of food and 57,000 pounds of ice had been donated. “We mahalo everyone who contributed, took food from their freezers… Government can’t do everything.”

It was a frank and candid analysis and, for a politician, not all that self-aggrandizing. The low number of survivors housed, for instance, seven days after the fire, raised a valid question as to whether enough was being done. As reported by Joshua Partlow in the Aug. 17 Washington Post, “many who lost homes and businesses in the blazes are camping on the beach. They are living, hour by hour, unsure of what the future holds.” Others, including kūpuna, have reported sleeping on golf courses, beaches and in cars.

In Contrast to Recent Disasters

By comparison, on Guam last May, an island that hosts a vast U.S. naval base to rival Pearl Harbor, the National Guard, Coast Guard, Air Force and Navy responded by sending the five-ship USS Nimitz Strike Carrier Group to assist in the recovery. (There were no fatalities in the storm.) For Hurricane Katrina, widely considered a failure of response, more than 60,000 servicemen were on the ground, including 18,000 active troops and 43,000 National Guard members, “first saving, then sustaining lives,” according to a Department of Defense summary.

Maui’s assistance did scale up in some respects. Under Biden’s disaster order, the federal government has been providing 20,000 meals a day through the Red Cross and other organizations.

But consider another recent disaster, Hurricane Ian in Florida last September. Four days before its projected landfall, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis requested that a federal disaster be declared, and Biden promptly approved it. FEMA immediately deployed a Defense Logistics Agency Distribution’s Expeditionary Team which, three days before the hurricane struck Fort Myers, was prepared with 836 trailers “filled with more than 13 million items,” as well as 438 trailers bearing water, and 234 carrying meals.

Yes, this is comparing apples and oranges. Ian was predictable and a classic wind, rain and storm surge event, not a hurricane of fire. Yes, Fort Myers isn’t an island. But there is no doubt that if Maui had received even a tenth of Ian’s aid in the first 48 hours, it would have made a huge difference to the lives of the displaced, the residents of West Maui, and ultimately to the government’s reputation.

Of course, we can’t put tractor-trailers filled with supplies on the interstate to Maui. That’s what Chinooks are for—the Army’s only heavy-lift cargo helicopter. Only, it seems we didn’t have them, or not enough of them.

Government Action

On Aug. 17, almost as if sensing the heat, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a statement from Pentagon Press Secretary Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder, announcing that, “almost 700 DOD personnel and 140 Coast Guardsmen are part of the coordinated response to the Maui.” The military members are working with members of FEMA, state and Maui officials on a “variety of missions.”

“DOD personnel are conducting six approved mission assignments at FEMA’s request. These include providing liaison officers and inter-island air and sea transportation for the movement of cargo, personnel, supplies and equipment.”

FEMA also asked the Army for space at Schofield Barracks on O‘ahu for support facilities for billeting, life support and hygiene facilities for federal emergency responders, Ryder said.

Service members and DOD civilians and contractors are also providing strategic transportation of personnel and cargo. In addition, personnel are on standby for aerial fire suppression. The U.S. Army Reserve is also providing a reserve center to FEMA as an incident support base and federal staging area, according to the DOD release.

SEE ALSO: Is the Water on Maui Safe After the Fires?

Facing a New Disaster Reality

So, while it doesn’t seem fair to fault the overall military response, the first 48 hours feels like a missed window. And if we still have people sleeping on the beaches two weeks later, something isn’t right.

Considering all of the above, maybe we’re being asked to retool our expectations when it comes to a major disaster, especially a fast and unexpected one like Lahaina. Maybe we need to vote for action and for restraints on our own appetites. Perhaps we need to shake off the attitude that assumes that in crisis, the government will be there in an hour with a whisk broom and a clean hotel room with hot running water. Because it feels a little First World, that attitude. And climate change has made clear we aren’t First World anymore, not when it comes to fires, floods and pandemics. We’re on an island far out in the Pacific, where fate means we should be each other’s own first responders.

Don Wallace is a contributing editor to HONOLULU. In 2002, he was the U.S. Naval Institute’s author of the year for his contributions to Naval History magazine.

Here’s the latest on what the Federal government is doing in the wake of the Lahaina fire.