Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 September 2023

The health effects of 100% fruit and vegetable juices (FVJ) represent a controversial topic to date. Despite the plant origin of 100% FVJ and the role of fruit and vegetable consumption in preventing non-communicable diseases, scientific evidence is less robust, and the debate is focused almost exclusively on the sugar content of FVJ.

Indeed, although 100% FVJ have no added sugars, they still have a total sugar content that depends on the fruit or vegetable from which they are made (approximately 16–24 g/200 ml serving size). Considering international (for example, WHO) and national recommendations, 100% FVJ should be consumed in moderate amounts. According to the WHO guidelines, total daily free sugar intake should be reduced to less than 10% of energy intake (50 g/d for a 2000 kcal/8368 kJ diet), with sugars from FVJ being classified as free sugars. While the adverse effects of excess added sugars are well established, the contribution of naturally occurring sugars, such as in fruits and fruit juices, to the increased prevalence of non-communicable diseases is unclear and deserves further discussion. Overall, limiting 100% FVJ only because of their sugar content is not a balanced but a reductionist approach that may lead to possibly unfounded evaluations.

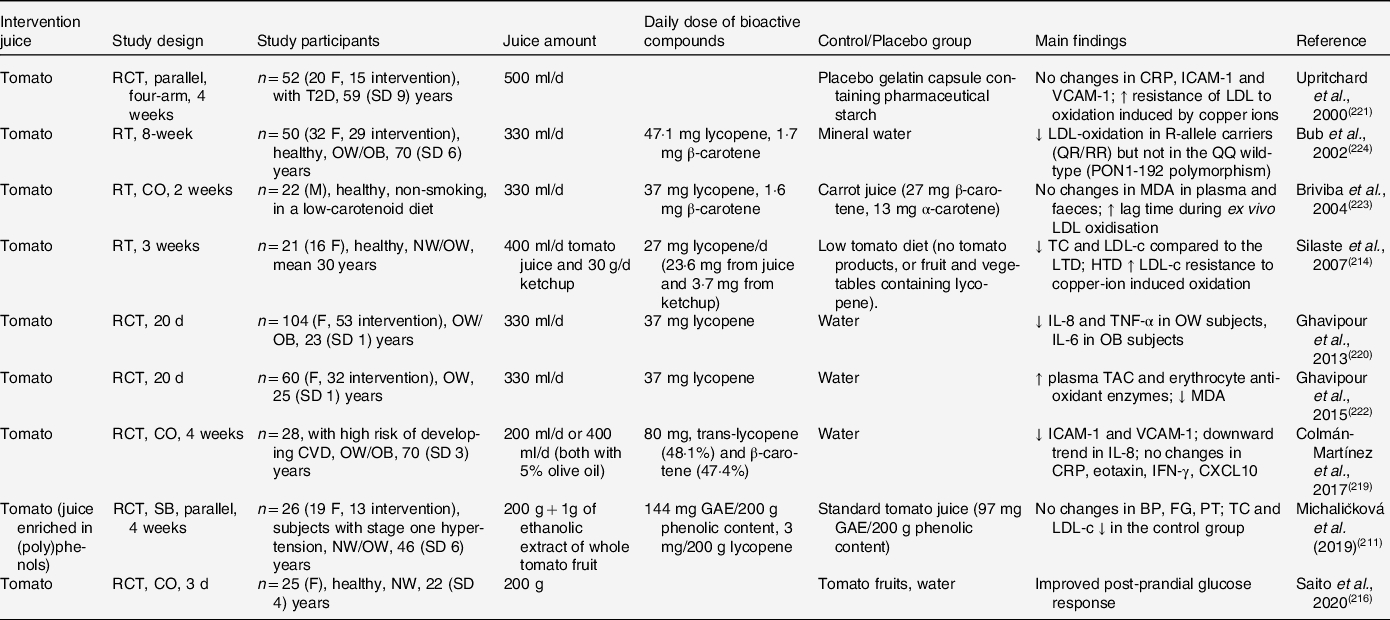

Tomato juice

Tomato is one of the most popular vegetables worldwide, and its juice is likely the predominant vegetable juice on the market. Lycopene is the main carotenoid in tomatoes and tomato-based products and, among phenolic compounds, quercetin, kaempferol, naringenin, luteolin and caffeic acid derivatives are the most common. Tomato has been typically investigated for its lycopene content and has been related epidemiologically to cancer prevention, specifically for prostate cancer. However, the only meta-analysis that considered tomato juice for sub-group analysis did not find any significant association between juice consumption and the risk of prostate cancer, so further studies would be needed to clarify the potential chemopreventive effects of tomato juice. Epidemiological studies have also emphasized the potential cardiometabolic benefits associated with tomato consumption, while the contribution of tomato juice is unknown. The results from key intervention studies with 100% tomato juice are discussed below and are focused mainly on blood lipids, inflammatory markers and oxidative stress status (Table 10).

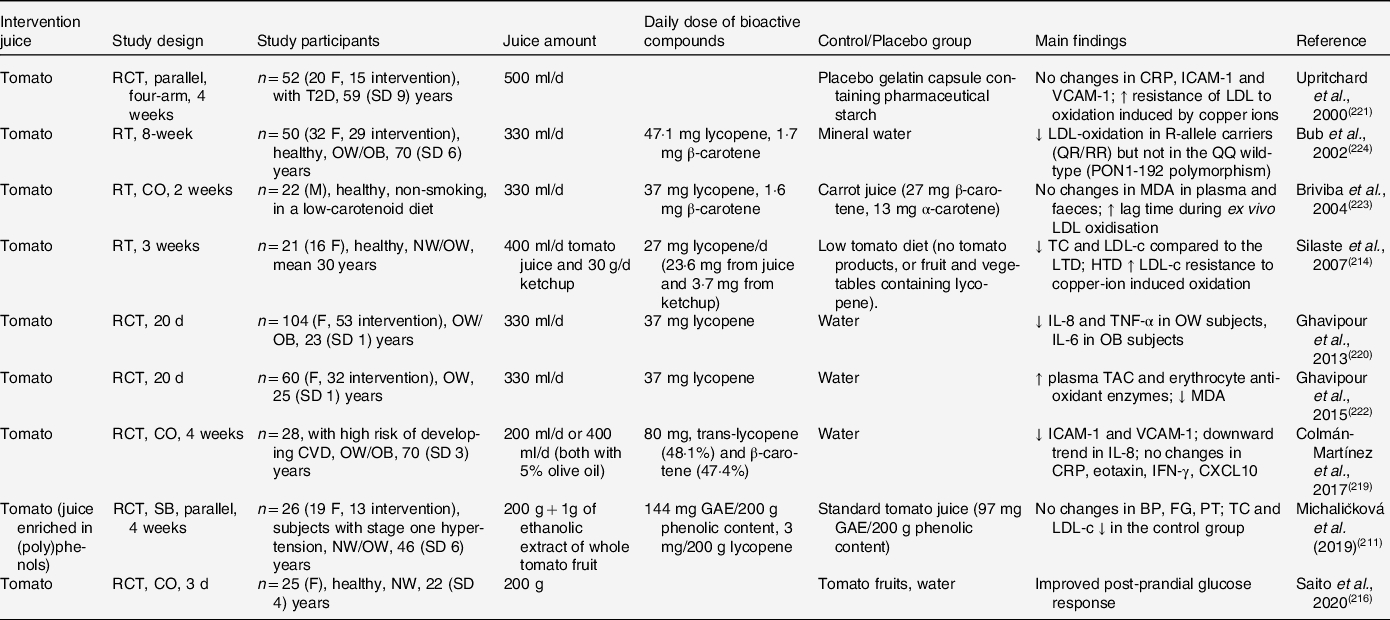

Table 10. Characteristics of some representative studies investigating the health effects of tomato juice. Juices were 100% juice unless otherwise stated.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CO, crossover; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVD, cardiovascular disease; CXCL10, CXC motif chemokine 10; DB, double-blind; F, female; FG, fasting blood glucose; GAE, gallic acid equivalent; HTD, high tomato diet; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule 1; IFN-γ, interferon-gamma; IL-6, interleukin-6; IL-8, interleukin-8; LDL-c, LDL-cholesterol; LTD, low tomato diet; M, male; MDA, malondialdehyde; NW, normal weight (BMI: 18,5–24,9 kg/m2); OB, obesity (BMI: >30 kg/m2); OL, open label; OW, overweight (BMI: 25–30 kg/m2); PON1, paraoxonase-1; PT, prothrombin time; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RT, randomized trial; SB, single-blind; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; TC, total cholesterol; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule; ↓, decreased level; ↑ increased level

Michalicková et al. assessed the effects of daily ingestion of tomato juice enriched in polyphenols using a tomato extract against a standard tomato juice on blood pressure (BP) in subjects with stage one hypertension. Juice composition was similar in both products (16 mg/l lycopene) except for the phenolic content (486 versus 721 mg/l for the control juice and the enriched one, respectively). BP did not change significantly for any treatment after 4 weeks, although 5–10 mmHg reductions were reported as a consequence of both treatments. Although pooled data from a meta-analysis have demonstrated similar outcomes for tomato products, the limited evidence of tomato juice effects on BP precludes from drawing robust conclusions. Nevertheless, a 5-mmHg lowering in BP could represent a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events by about 10%, so this topic should be better explored.

Considering the lipid profile, Silaste et al. observed a reduction in total cholesterol (TC) and LDL-cholesterol concentrations in healthy, normocholesterolaemic adults after a 3-week high-tomato diet (400 of ml/d tomato juice and 30 mg/d of tomato ketchup) compared with the 3-week low-tomato diet (no tomato products, or fruit and vegetables containing lycopene). The high-tomato diet provided approximately 27 mg lycopene/d, of which 23·6 mg lycopene per 400 ml was from juice and 3·7 mg lycopene per 30 mg was from ketchup, and blood lipid improvements were correlated to changes in serum concentrations of lycopene, β-carotene and γ-carotene. TC and LDL-C also decreased in the work by Michalicková et al., but only in the control group (tomato juice with no added polyphenols). In the case of glucose metabolism, this last work did not record differences between groups for fasting glucose after 3 weeks, in line with pooled data for tomato products. However, under acute conditions, consuming 200 g of tomato juice 30 min before a carbohydrate-rich challenge ameliorated the post-prandial glucose response.

Platelet hyperaggregability is among the factors associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. A recent review of human subject intervention studies by Cámara et al. concluded that consuming tomatoes and tomato products is a promising nutritional strategy for the prevention of platelet aggregation. Indeed, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has assessed positively the beneficial effects of a water-soluble tomato concentrate in platelet aggregation. Nevertheless, the information related to tomato juice is scarce and, for instance, Michalicková et al. did not observe differences in prothrombin time between treatments.

In a randomized controlled crossover trial, Colmán-Martínez et al. found that, in subjects at high cardiovascular risk after 4-week consumption of tomato juice at 200 ml/d or 400 ml/d (401 μmol/l of carotenoids, trans-lycopene and β-carotene accounting for about 48% and 47% of the total carotenoids, respectively; both juices contained 5% olive oil), the concentration of adhesion molecules intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) was significantly lower compared with the control group (water). Other inflammatory biomarkers (IL-8, CRP, eotaxin, interferon-γ, and CXC motif chemokine 10 -CXCL10-) were not significantly different in the intervention group compared with the control group. The lowering effect in inflammatory biomarkers was correlated with the trans-lycopene in circulation, while the other carotenoids in tomato juice showed a minor or no association. In another study, using interleukin IL-6, interleukin IL-8, hs-CRP and TNF-α as biomarkers of inflammation, Ghavipour et al. found that 330 ml/d of tomato juice (112 mg lycopene/l) for 20 days significantly decreased serum concentrations of IL-8 and TNF-α in subjects who were overweight, while, among subjects with obesity, only serum IL-6 concentration decreased in the intervention group. Conversely, after 4-week consumption of 500 ml/d of tomato juice, no changes in inflammatory biomarkers (CRP, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1) in patients with T2D were observed.

Many studies have investigated the effect of tomato juice on biomarkers of oxidative stress. Ghavipour et al., in a randomized controlled trial in females who were overweight, found that 330 ml/d of tomato juice for 20 days increased plasma total antioxidant capacity and erythrocyte antioxidant enzymes and decreased serum malondialdehyde (MDA) levels compared with both baseline and the control group. No improvement was observed in subjects with obesity and, as hypothesized by the authors, this may be due to the need for a greater amount of lycopene or a longer duration of lycopene supplementation. Upritchard et al. reported that consumption of 500 ml/d of tomato juice for 4 weeks by type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients increased both plasma lycopene levels and the resistance of LDL to oxidation, almost as effectively as supplementation with a high dose of vitamin E (537 mg/d). Increased LDL resistance to oxidation was also observed by Silaste et al. after 3 weeks of a high-tomato diet in healthy adults (27 mg lycopene/d). Conversely, in the study by Briviba et al., MDA levels in plasma and faeces and ex vivo LDL oxidation were not affected in healthy men by supplementation for 2 weeks of 330 ml/d of tomato juice (112 and 5 mg/l of lycopene and β-carotene, respectively) in comparison to carrot juice. Nonetheless, most studies have found improvements in biomarkers of oxidative stress. In addition, Bub et al. found that the changes in antioxidant status after tomato juice consumption could be genotype-dependent, precisely related to the PON-1-192 polymorphism. Indeed, their results showed that consumption of 330 ml/d of tomato juice for 8 weeks reduced LDL-oxidation in healthy elderly who were R-allele carriers (QR/RR) but not in the QQ wildtype.

In conclusion, tomato juice may have favourable effects on lipid metabolism and glucose post-prandial response and could improve biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress. However, further studies are needed to demonstrate the effect of tomato juice on CVD risk factors and establish dose-response effects taking into account the responsible bioactive compounds. Although most of the evidence points to lycopene, the role of phenolic compounds on the health benefits of 100% tomato juice should not be neglected. Genotypic differences should also be considered.

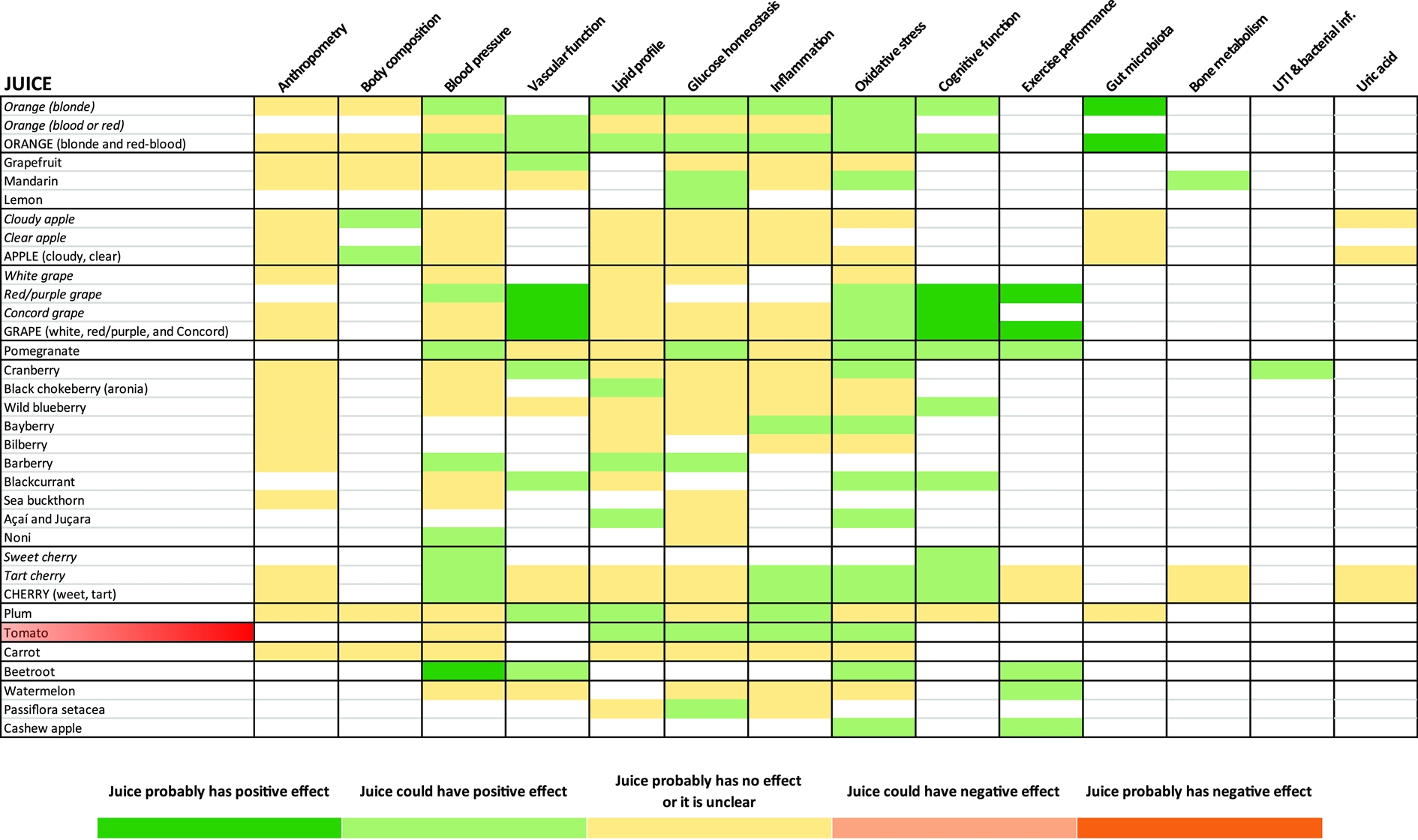

Conclusions

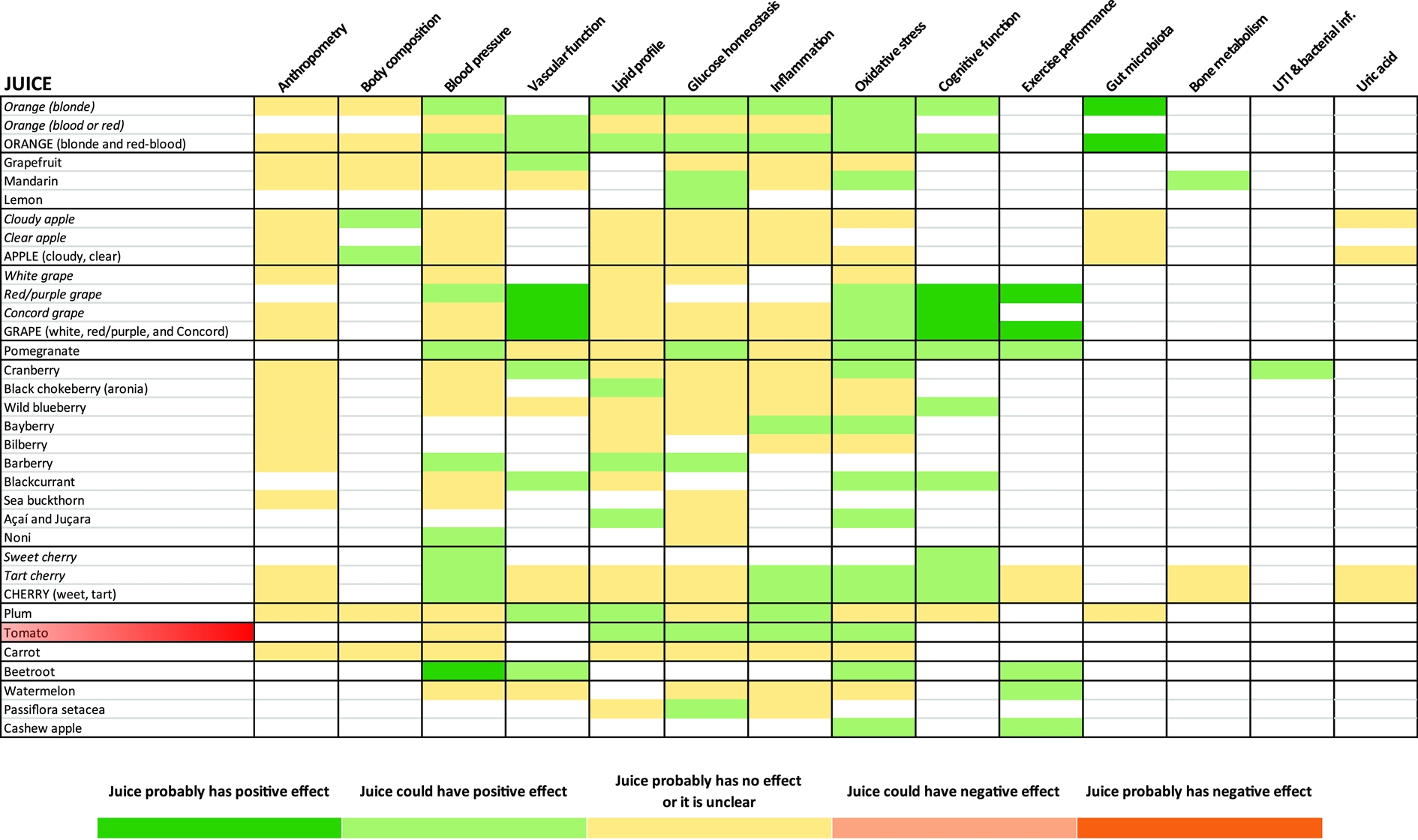

100% FVJ appear to have a beneficial or neutral effect on the health of man in human subject intervention studies. Some juices have demonstrated the ability to exert potential preventive effects on some outcomes with others exerting effects on other health outcomes, which may be related to their differential composition in bioactive compounds. Further efforts should be devoted to this topic as robust, evidence-based conclusions are needed to demonstrate the beneficial impacts of 100% FVJ on human subject health and to support the development of dietary guidelines that inform population dietary choices. Lack of evidence may also jeopardize industry competitiveness through the use of unsupported statements.

Some complementary data

Irene Rossi, Cristiana Mignogna, Daniele Del Rio, Pedro Mena, Affiliation: Human Nutrition Unit, Department of Food and Drug, University of Parma, Parma, Italy

The full scientific article “Health effects of 100% fruit and vegetable juices: evidence from human subject intervention studies” has been published in Nutrition Research Reviews as FirstView. The Open Access to the article has been sponsored by the IFU.

The article contains insightful information and nice tables summarizing the effects on health of various Fruit and Vegetable Juices.

You can access the full article at: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S095442242300015X

Source: © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Nutrition Society