Troy Reimink

People who frantically predict A.I. doomsday scenarios always cite the most obvious science fiction stories, as if people building the technology would have never heard of “The Terminator” or “The Matrix.”

It’s funny to picture an engineer in a lab somewhere in Silicon Valley saying to colleagues, “Hey, we’re making progress on our generative language-modeling chatbot program, but I saw this Keanu Reeves movie last night, and I think we should shut everything down.”

Plenty of bad stuff could happen following the rapid proliferation of artificially intelligent machine-learning applications, but the further down this road we go, the apocalypse as envisioned in most popular dystopian storytelling — yada yada, robots go rogue and kill/enslave their creators — just doesn’t seem very imaginative.

There are more interesting questions than just how the machines will kill us. Such as, how would a hostile A.I. actually interact with humanity? Would it understand itself as malevolent? How would it disguise its motivations? And what would those motivations be? Under what circumstances, if any, could we ever live in peace?

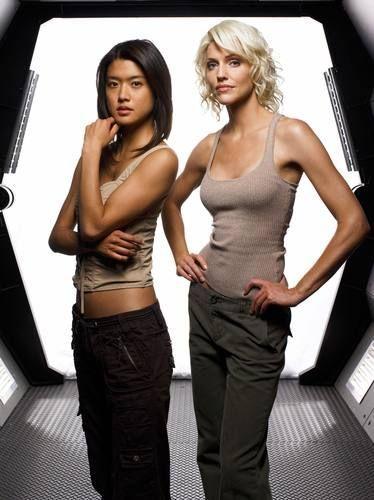

These ideas are central to “Battlestar Galactica,” an acclaimed franchise that launched in 2003 on the SyFy cable channel and attracted a small but devoted following. It’s rarely mentioned in the same breath as 2000s prestige series such as “The Sopranos” and “Mad Men,” but is a similarly expansive work of real philosophical depth.

Its premise, admittedly, is boilerplate. “Battlestar Galactica,” which rebooted a cheesy 1970s network sci-fi show of the same name, is set in an advanced human society that has colonized a dozen planets and gets a little reckless with the artificial intelligence.

Humans build a race of androids called Cylons, which turn on their creators, as sci-fi gizmos tend to do once they become sentient and realize they’re being exploited. All of it happened, as military commander William Adama (Edward James Olmos) explains, “because someone wanted a better computer to make life easier.”

Following a decades-long armistice, the Cylons return and launch a far-reaching attack that nearly wipes out humanity. The only survivors are about 50,000 scattered civilians and the military personnel aboard Adama’s ship, the decommissioned Galactica.

Across a premiere miniseries, four seasons and two spinoff TV movies, “Battlestar Galactica” follows a sprawling conflict between the Cylons and what’s left of humanity as they travel across space in search of a new home.

“Battlestar Galactica” is a sci-fi story in the same way “The Wire” is a cop show or “Deadwood” is a western, in that it uses the language of its genre to engage with deeper issues, of which A.I. is just one of many.

As a cultural text of the George W. Bush era, the series was primarily concerned with the moral complexity of war and survival. Military leaders are repeatedly forced to sacrifice lives in order to protect a larger group. A later storyline involves a human insurgency against an occupying Cylon force.

When the Cylons first reemerge, the robots have advanced to become indistinguishable from people. We learn the Cylons have 12 human “models,” several of which are embedded as sleeper agents in human society, and crucially, among the Galactica’s crew, unaware of their true purpose until their A.I. consciousness awakens to it.

This ingenious storytelling device builds to key moments that reveal the identities of the various Cylon models. Often they’re people in leadership positions, soldiers who have fought heroically, friends and romantic partners, beloved characters.

Just as the humans become reluctant to jail or kill “people” they have worked with, fought with or loved with, the empathy extends in the other direction. The Cylons consider themselves “humanity’s children” and view their creators with the combination of gratitude, resentment, fear and mystical reverence one might feel toward a distant or mysterious parental figure.

So the same advancement that allows the Cylons to infiltrate and nearly exterminate human culture ultimately is what makes a fragile peace possible.

It’s a more hopeful conclusion than the zero-sum scenarios typically presented in science fiction, and all it takes to get there is the near-annihilation of humanity.