The Tragic Story Of The Photographer Who Documented The Renegotiations Of German Reparations

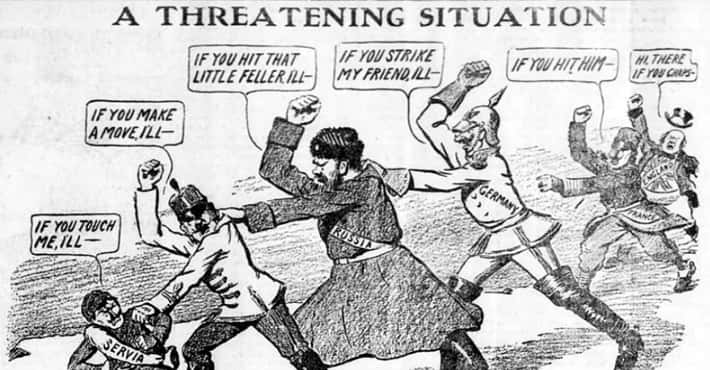

In the aftermath of WWI, world leaders gathered to make sense of the momentous event and decide how to move forward from it. At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and 1920, the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Japan, and Italy established terms for peace with additional restrictions and expectations placed on Germany. Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, the so-called War Guilt Clause, detailed the demilitarization of Germany alongside massive reparation payments Germany would make to Allied nations.

More than a decade later, the issue of reparations was still being hashed out, this time at the Hague in the Netherlands. When representatives from Allied nations and Germany met behind closed doors in 1930, photojournalist Erich Salomon caught the foreign dignitaries in an unscripted moment, one that captured the attention of the public worldwide.

The Early Life And Career Of Erich Salomon

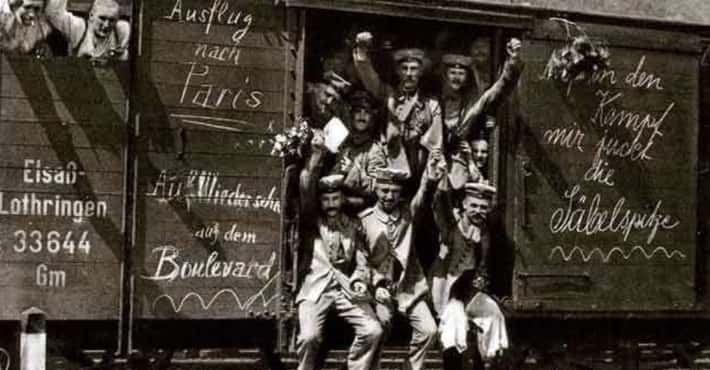

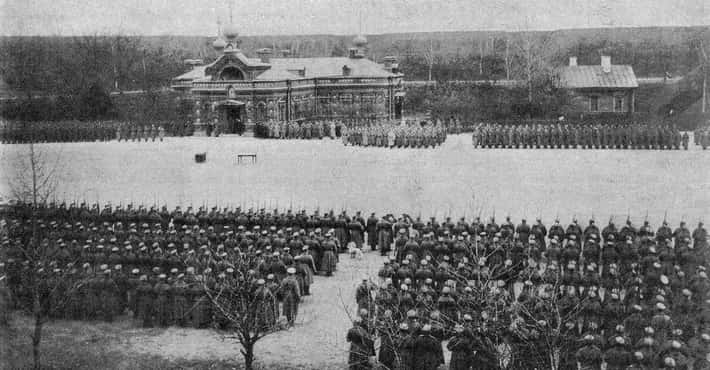

Article ImageBorn in 1886 in Berlin, Erich Salomon studied zoology, engineering, and law at university, eventually earning a doctorate in law from the University of Munich in 1913. During WWI, Salomon was drafted into the German army, only to be captured by the French at the First Battle of the Marne and held as a POW for almost four years.

After WWI, Salomon returned to Berlin where he worked a multitude of jobs before taking a position with Ullstein publishing in 1925. The following year, Salomon purchased a Ermanox camera. The small camera allowed for pictures in poor light, a novelty at the time. Salomon quickly transitioned to the Leica, a 35-millimeter camera.

In 1928, Salomon snuck his small camera into the courtroom of a slaying trial - either under his hat or in a briefcase - capturing impromptu moments not meant for the public. He sold the images to German newspapers, making a name for himself as a candid photographer. He developed a system:

First, arrive late. Second, dress well. Third, speak in an unintelligible tongue. If they can't understand you, they will assume you are supposed to be there.

Salomon's photographs, his resourcefulness, and his ability to capture his subjects in truly human moments led to international attention. French Premier Aristide Briand called him the "king of the indiscreet," while officials soon joked that meetings could not "begin without him, or people will think that our talks are unimportant."Article Image

German Chancellor Hermann Müller wrote a letter to Salomon, praising his photographs from a recent meeting of the League of Nations. Müller expressed "the greatest admiration" and told Salomon:

Your photographs gain greatly in value by the fact that one is nearly always unaware of your picture-taking, and that you use no flashlight, even in artificial light. These circumstances lend your pictures the charm of complete naturalness.

By 1930, Salomon was able to get closer to his subjects than any of his colleagues, giving him the ability to take pictures of celebrities, orchestra conductors (with whom he was enthralled), and world leaders in Europe and the United States.

The Hague, 1930

Salomon's attendance at international conferences was nothing new, and when world leaders met in 1929 and 1930 to negotiate Germany's reparation payments, Salomon was there. Under the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was responsible for 132 billion gold marks in reparations, but massive inflation and a general economic collapse necessitated renegotiation. The Dawes Plan, named for banker Charles G. Dawes, reorganized Germany's debt and allocated loans from the United States and Britain to aid Germany's economy. Reparations were reduced as well but, in 1929, Germany again struggled to pay. Article Image

The outcome of the series of meetings that took place at The Hague in 1929 and 1930 was the Young Plan, a new path forward for Germany with reduced payments and more international financial assistance. As the plan came to fruition, foreign dignitaries spent long days and nights hammering out the details. At a restaurant called Anjema, Salomon reportedly hid behind curtains for hours until his desired to photograph European dignitaries.

When Salomon's shot from behind the scenes at The Hague was published in the London Graphic, they purportedly coined the term "candid camera." The shot, taken at 2 am, created a sense that one "had been present at this momentous meeting," giving the public glimpse of the "weary eyes... slumped... dozing" pillars of power.

On To The White House

After photographing the momentous event, Salomon made a trip to the United States, famously taking a series of photos of Marlene Dietrich as she appeared to make a phone call.Article Image

He also took numerous pictures of William Randolph Hearst at his San Simeon estate. Because Salomon kept the company of foreign dignitaries, he gained access to the White House in 1931. According to Time magazine, "President Hoover might never have allowed "Dr. Erich 'Candid Camera' Salomon in the White House if Premier Pierre Laval of France had not politely insisted."

As Laval and Hoover posed next to one another in the Lincoln Study, Salomon struggled to get a candid shot. He told the two men to simply talk and, as they did, Salomon got his shot. Laval reportedly said to President Hoover, "I told you, Mr. President, how it would be. I know his ways."

As the first foreign photographer to work in the White House, Salomon was at the height of his career in 1931. He published a collection of his photographs, Famous Contemporaries in Unguarded Moments, that same year. Alongside publication, he threw an elaborate party at the Hotel Kaiserhof and entertained guests with a slide show of his work.

Salomon's Final Years

Article ImageSalomon continued to travel, but when he returned to Berlin in 1931, he was met by the rise of Adolf Hitler and his party. As a Jew, Salomon was forced to flee his native Germany, taking up residence in the Netherlands in 1932 or 1933. His wife was a Dutch citizen. Salomon spent years taking pictures throughout Europe until the Third Reich captured the Netherlands in 1940. Salomon and his family, unable to escape, were now subjected to the yellow star worn by Jews throughout the Reich. They went into hiding but were taken in when their location was revealed to authorities.

Salomon was taken in and deported, first sent to Theresienstadt and then to Auschwitz. Salomon, his wife, and his son, Dirk, passed in the gas chambers at Auschwitz in July 1944. Salomon's oldest son, Peter Hunter (who changed his name from Otto Salomon), fled to England.

The Legacy Of Erich Salomon

As a soldier during WWI, the photographic historian of post-WWI life and politics, and an innovator in the field of photojournalism, Erich Salomon had a relatively short career in the field, but his ability to capture intimate moments without detection brought him international acclaim. His techniques pushed convention, seen through the award that bears his name - the Dr. Erich Salomon Prize given for lifetime achievement by the German Society for Photography - honors by acknowledging his "vision and standards of value [that] still form the norm around which a critical profession orients itself."