Hokusai’s Manga

May 11, 2015 · 0 comments

By Ellis Tinios.

Hokusai manga was one of the great publishing sensations of 19th-century Japan, issued serially between 1814 and 1878. After the opening of Japan to foreign trade in the 1850s not long after its creator’s death, it rapidly became the best known Japanese book in the wider world. Copies were circulating in Paris is early as 1856, and in 1867 the Shogun’s government sent the 14 volumes then comprising the set to Paris for display at the Exposition universelle d’art et d’industrie of that year. Today it remains widely know in the West, by title if not by content.

Hokusai manga was one of the great publishing sensations of 19th-century Japan, issued serially between 1814 and 1878. After the opening of Japan to foreign trade in the 1850s not long after its creator’s death, it rapidly became the best known Japanese book in the wider world. Copies were circulating in Paris is early as 1856, and in 1867 the Shogun’s government sent the 14 volumes then comprising the set to Paris for display at the Exposition universelle d’art et d’industrie of that year. Today it remains widely know in the West, by title if not by content.

The global recognition accorded Hokusai manga belies its modest origins: it was originally published in 1814 “complete in one volume” by Eirakuya, a provincial publishing house based in Nagoya. It is unlikey that either the artist or the publisher anticipated its astonishing popularity. Nor would they have expected it to evolve into a highly lucrative title that would eventually run to 15 volumes and remain in print for a century.

An Eirakuya advertisement of 1814 for “copybooks” (edehon 繪手本), i.e. How-To manuals for the aspiring artist, provides the first mention of Hokusai manga. It appears between two companion volumes from the brushes of two of Hokusai’s contemporaries. All three books present numerous small-scale studies and are offered for sale “complete in one volume”. Closed they measure 23 x 16 cm and are printed in limited ranges of colours. Adulatory prefaces are the only running texts in them. In the case of Hokusai manga, the preface runs to 250 words. It praises Hokusai’s unparalleled ability to “transmit the spirit” of all that he depicts, describes the circumstances leading to the creation of the book, outlines it contents and concludes “Those who really wish to learn to draw can hardly do better than take this book as their guide.”

We learn from the preface that Hokusai had traveled to Nagoya in the autumn of 1813, where he delighted his desciples by producing a ceaseless flow of images of all imaginable things in heaven and on earth. Those sketches were gathered together and prepared for publication as Hokusai manga by Bokusen and Hokuun, two of his pupils.

In promotional material, Eirakuya restates that “Hokusai manga is an excellent copybook.” Scores of such copybooks had been produced in Japan for over a century beforehand. Collectively, such books represented the commercialization and popularization of the practice of art in Japan in the course of the 18th century. Any aspiring amateur could learn from them instead of paying a teacher for tuition — or so the publishers claimed in their blurbs. But such an amateur would have had to have had ample reserves – a single Hokusai manga volume cost the equivalent of a day’s wages paid to a skilled carpenter.

In other words, on its first appearance, Hokusai manga was just another copybook in a long tradition of such works. It was Hokusai’s earliest venture into this genre. It owed a great debt to the copybooks designed by his contemporaries. Its publication was a speculative venture by a long-established Nagoya publisher, Eirakuya.

In other words, on its first appearance, Hokusai manga was just another copybook in a long tradition of such works. It was Hokusai’s earliest venture into this genre. It owed a great debt to the copybooks designed by his contemporaries. Its publication was a speculative venture by a long-established Nagoya publisher, Eirakuya.

Demand was so great that in 1815 a second set of printing blocks were cut for what was now being called “Part I” of Hokusai manga. The new set of blocks included name tags for the historical and literary Chinese and Japanese figures that appear in the book. The addition of these tags made the content more widely accessible — which in turn made the book more marketable. All subsequent Hokusai manga volumes were published with tags identifying all the figures, objects and scenes depicted in them. Adverts announced that the series would run to ten volumes; between 1815 and 1819 that goal was achieved.

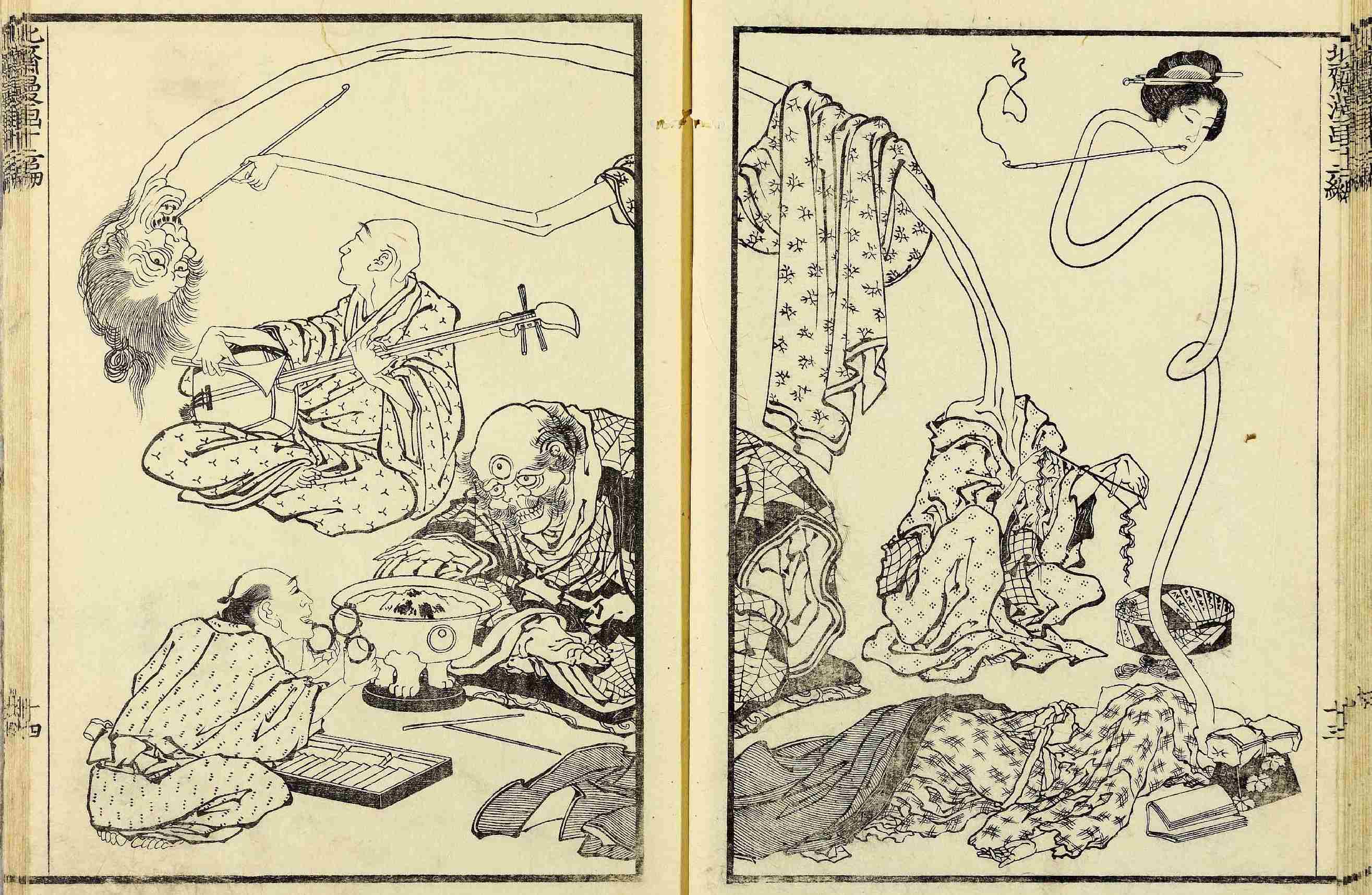

In 1815, in addition to the second set of blocks to print Part I, blocks were cut for a Part II and Part III. Parts IV and V appeared in 1816; Parts VI through IX in 1817; and Part X in 1819. The basic format was the same for each Part: approximately sixty pages covered with multiple images printed in line and over-printed with pale pink and pale gray. In the back matter (colophon) of each of volume various Hokusai pupils are named as responsible for selecting, editing, copying, and assembling the contents.

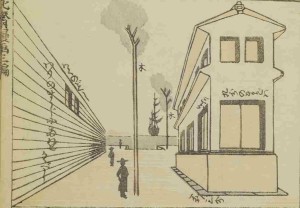

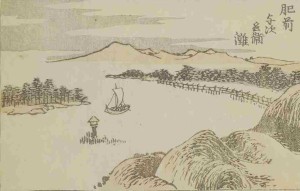

In Part I, Hokusai provided encyclopedic coverage of the human and natural world. In doing so he followed the example of earlier copybooks. Part Two is similar in content: it too provides encyclopedic coverage of the human and natural worlds and, additionally, the material world. None of the further Parts offer as expansive a range of subjects as the first two. In the later parts Hokusai — and his collaborators — allow certain themes to dominated particular volumes: landscapes, temple architecture, nature studies, or martial arts. Another change was a general increase in the size of the figures from Part III onward. Nonetheless, each volume still presented a dazzling array of subjects.

In Part I, Hokusai provided encyclopedic coverage of the human and natural world. In doing so he followed the example of earlier copybooks. Part Two is similar in content: it too provides encyclopedic coverage of the human and natural worlds and, additionally, the material world. None of the further Parts offer as expansive a range of subjects as the first two. In the later parts Hokusai — and his collaborators — allow certain themes to dominated particular volumes: landscapes, temple architecture, nature studies, or martial arts. Another change was a general increase in the size of the figures from Part III onward. Nonetheless, each volume still presented a dazzling array of subjects.

After a hiatus of nearly fifteen years—in 1834—Hokusai manga, Part Eleven appeared. In promotional literature Eirakuya announced that a further ten parts were planned so that when completed, Hokusai manga would run to twenty parts. Only Parts XI and XII of the second group of ten saw the light of day. Part XI is very much like the earlier volumes in terms of variety of content, scale and layout.

Part XII is anomalous in many significant ways. If this remarkably witty collection of visual puns had appeared under another title, no one would have asked why it was not published as one of the manga. It stands apart with its comic—often satiric—and even surreal—images of weird encounters between gods, heroes, goblins, warriors, peasants, and commoners—with beasts and creatures of all sorts. Additionally, it was published in line only, unlike all the other manga volumes, which were published in line with pink and grey tints.

We must understand that not all—or even most—of those who purchased copies of the Hokusai manga—and other titles—were aspiring artists who intended to use them as copybooks. These volumes possess sufficient intrinsic interest for a wider public to wish to possess them simply as books crammed with fascinating pictures; books to browse through again and again, discovering something new each time. The Hokusai manga were not unique in this respect. Many other such ‘picture books’ were also consumed in this way in the Edo period. Publishers’ blurbs and prefaces often comment on how “perusing one of these books will raise the spirits of the amateur and delight the connoisseur.”

We must understand that not all—or even most—of those who purchased copies of the Hokusai manga—and other titles—were aspiring artists who intended to use them as copybooks. These volumes possess sufficient intrinsic interest for a wider public to wish to possess them simply as books crammed with fascinating pictures; books to browse through again and again, discovering something new each time. The Hokusai manga were not unique in this respect. Many other such ‘picture books’ were also consumed in this way in the Edo period. Publishers’ blurbs and prefaces often comment on how “perusing one of these books will raise the spirits of the amateur and delight the connoisseur.”

After the appearance of volume XII in 1834, no further Hokusai manga were issued in the artist’s lifetime. He died in the spring of 1849. In the autumn of that year Eirakuya published Hokusai manga, Part XIII. This was a blatant attempt on the part of the publisher to cash in on renewed interest in the artist generated by his death. The publisher claimed that Hokusai had provided him with all the designs that appear in Part XIII. We can be sure that it was issued without any editorial imput from the artist. At that late date, Eirakuya continued to circulate notices promising that the series would run to twenty parts. Toward that end, in the early 1850s, Part XIV appeared for sale. A quarter of a century later—in 1878, the firm published Hokusai manga, Part XV. The then head of the firm proudly—if mendaciously—announced that with the publication of Part XV, he was fulfilling his father’s goal of extending the Manga series to fifteen volumes.

The three posthumous manga—of 1849, c.1852 and 1878—demonstrate the opportunism of publishers. Eirakuya claimed they were using drawings left by the master for all three books. In fact, all three were produced by pupils and others who were familiar with Hokusai’s idiom. The images in them offer a pale reflection of anything Hokusai himself would have coutenanced; they betray a very different aesthetic. But such was the pull of the name Hokusai that there was a ready market for these pastiches.

Ellis Tinios is the author of Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-e in Edo 1700-1900, available now from the British Museum Press.

Miss Hokusai will be released by Anime Ltd as an Ultimate Edition Blu-ray/DVD set as well as on Blu-ray and DVD from 14th November 2016.

Leave a Reply